Luscious 180 gram vinyl, that sounds as great as it looks. Subject to availability.

Back in December I started off by referring to the already fox eared pages of my 2026 diary. There’s a good reason for it. At the end of 2025 we had finally released the Fabulous Thunderbirds set of recordings from their early days along with a Bobby Charles album and a previously unheard Lonnie Mack record. Well that little herd raised some dust and we already have more where they came from to bring to you later in 2026 and these things take a lot of forward planning.

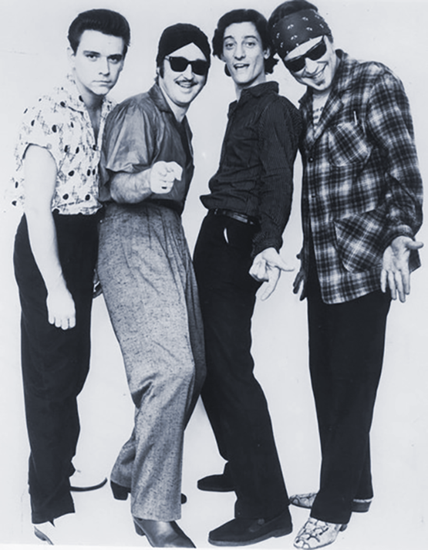

Starting with the Fabulous Thunderbirds I can tell you that we are bringing you eight studio albums in 2026 (on 12” blue vinyl) – all from the era when Jimmie Vaughan and Kim Wilson were tearing it up out front between 1978 and 1989. It’s all the albums that are in the CD set – The Jimmie Vaughan Years: Complete Studio Recordings 1978 -1989

Those upcoming vinyl albums are:

The Doc Pomus Sessions (previously unreleased)1978

The Fabulous Thunderbirds (Girls Go Wild) 1979,

What’s The Word? 1980,

Butt Rockin’ 1981,

T-Bird Rhythm 1982,

Tuff Enuff 1986,

Hot Number 1987,

Powerful Stuff 1989

Now the big news: we are making a limited edition LP box set with the 32 Page book from the CD collection that will be available to pre-order for delivery in November 2026.

Additionally, we have a fantastic live album Live In London 1985 which is on a 2LP set also available as a CD/DVD set. The quality of the recording and filming is excellent and this is a rare opportunity to witness what the band was like at the height of the Jimmie Vaughan era.

We were going to bring you a new Dan Penn album in March this year but it got put back to 17th April to ensure that the vinyl was delivered on time. It is called Smoke Filled Room and it is the fruit of his most recent review of the best of his previously unreleased demos. Dan’s soulful voice and southern groove are a formidable combination and his fans around the world are going to love this.

Also on the starting line for April is a new album by Dirk Powell. With deep Kentucky roots, this in-demand American fiddler, banjo player and singer now based in Louisiana doesn’t release many records under his own name but when he does, they are always worth the wait. Wake is his first for six years and it is a musical journey like no other. We’re proud to have him on the label.

Having put on some impressive muscles since its early birth early in 2023, Bill Kirchen’s studio album Cat Out Of The Bag is snorting and stamping in the Last Music stables and finally fit for the races. You’re not gonna believe how good this one is. We’re aiming to throw off the bolt for a May release and will be telling you more about this soon. It’s another winner without a doubt and miraculously, it’s left no manure!

Last Music is a sponsor of Folk Alliance International 2026 in New Orleans in January. Lisa and Alice will be there for the whole event and will welcome a chance to tell you more about our plans at our booth number 504.

January 2025 Selections